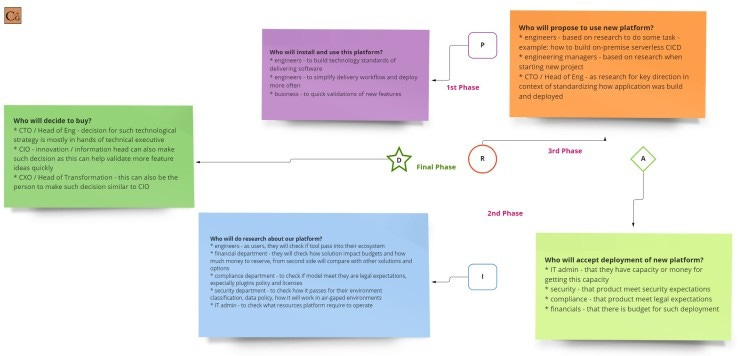

[RBM] Whom to engage on examples.

As promised in my last article from the RAPID-based Modernization series, this post will showcase examples of how to identify which people to engage in the decision-making process and what specific questions to ask them.

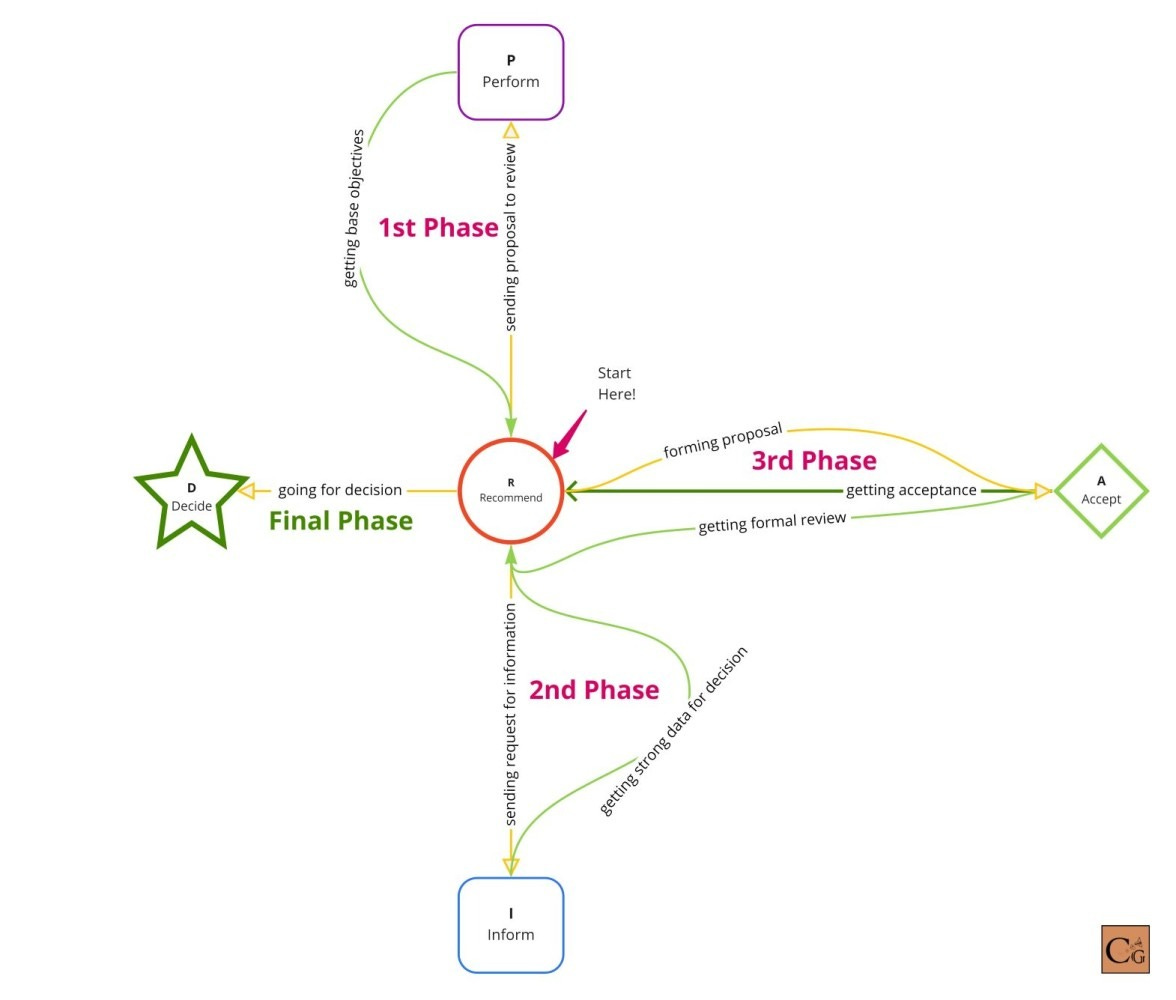

Let's start with a small reminder of what we described last time, then clarify which roles should answer what types of questions.

Let's follow the RPIAD sequence I suggested. You can ask these types of questions here:

For "R" - "Recommendation" - Who can propose and gain acceptance for your initiative with you? Who are your allies in getting this idea approved?

For "P" - "Perform" - Who will actually use it? Who will implement it? How will this impact these groups of people? Consider the day-to-day users and implementers.

For "I" - "Inform" - Who will have any contact with our system? Who could be a potential reviewer or source of information in the decision-making process? Think about stakeholders who need to be kept in the loop.

For "A" - "Approval" - What formal acceptance does the project need to start? Which sign-offs are required before proceeding?

Finally, for "D" - "Decision" - Who is the decision maker? And importantly, who is the REAL decision maker with actual authority to give the final go-ahead!

Alright, let's move on to some examples now.

We will get two cases at the same time. The first one involves a process modernization project, while the second focuses on implementing a new system. Let's make some assumptions for each project to provide more context.

The first project - the modernization one - is replatforming a complex CRM platform. This CRM connects with thousands of systems and serves as the only CRM used in the organization. A dedicated team maintains this system, handling everything from development and delivery through support. The platform is a self-created monolithic software that's almost 20 years old. It runs on Virtual Machines in the company's own datacenter. The company now aims to run Kubernetes-based environments in the cloud and build software based on microservices.

The second project involves implementing a new CI/CD center of excellence. The company wants to unify CI/CD systems and build a team that will provide an easy-to-use platform for development teams. The goal is to eliminate dedicated Delivery teams from every development initiative.

You might think both initiatives are purely technical, but that's a misbelief. The first initiative aims to modernize the technology stack while creating space for much faster delivery of new features in a critical system. It's also designed to reduce the outflow of technical specialists who leave for more attractive technologies and better salaries elsewhere. The second initiative is similar in nature. By standardizing the software delivery platform, the company wants to achieve several business goals, including reducing project costs and delivery time for new initiatives. Currently, the average project spends its first 4 months building the delivery layer. The company anticipates these changes will reduce the timeline of every project by 3.5 months.

This provides only basic context for our cases. As we go through each area of the RAPID framework, we'll drill deeper to help visualize significant aspects of these projects.

Let's start with our RAPID sequence order.

The first letter is "R" which stands for "Recommendation." There is always someone who introduces projects in a company. Possibly, it's you, my reader.

In the first project, it was the CRM owner, the Director of Internal Services.

After 10 consecutive feature requests were declined during analysis, he concluded they needed to propose rebuilding the platform from scratch. Simultaneously, this would allow migrating the system to the cloud—aligning with the new company direction set by the CTO. This initiative aims to improve system performance, which represents the second-biggest problem with the current platform.

In the second project, the idea came from a CI/CD team leader who had been responsible for four nearly identical systems for about a month. He identified significant redundant work that couldn't be simply merged. The current system lacks sophisticated ways to address this problem, primarily because the underlying technology is outdated.

This perspective is particularly valuable to us—why? Because identifying such individuals allows us to transform more people into recommenders who can drive similar insights and improvements.

In the first case, we can transform Sales department users of our CRM into powerful recommenders. They'll gain significant advantages from the migration, as the new system will deliver their needed features. We can also recruit sub-recommenders, such as members of the Infrastructure department. If this represents the company's first cloud migration, the Infrastructure team might be eager to showcase a project demonstrating the benefits of this approach.

In the second case, the most obvious recommenders would be other CI/CD team leaders who likely struggle with the current platform. However, this group might lack sufficient influence to drive such a decision, as they's far from C-level decision-making. In this scenario, it would be beneficial to identify a second recommender similar to the main recommender in the first case - perhaps a director-level stakeholder whose goals are being hindered by limitations of our current platform.

Let's jump from "R" into "P" for "Perform" – the implementers. This group is critical not only in the decision process but throughout the entire journey. If we don't engage them in decision-making, they can block or even kill our idea, since they're ultimately responsible for implementation. You need to discover their needs, aspirations, and concerns that your proposition can address. This is the most effective action you can take to ensure your idea gets executed. Let's examine how to identify them in our cases.

In the first case, we'll encounter various user groups. We start with the sales department members – both the sales representatives and their management, who want visibility into individual sales activities. Then there's the team that will develop and maintain the system, who are users of the code and platform built in this process. Finally, we have teams on the edge, like infrastructure or CI/CD teams, that need to adapt to the new environment. All these people will use what the project creates and must engage during implementation.

In the second case, we can simplify our view since the most important users will be CI/CD-responsible members – typically DevOps team members and developers who are the end users of this system. We should also include their management and product owners, who need to know and control where requested features will be deployed.

This section might seem straightforward, but remember – it represents one of the most influential groups in your project's success.

Next group letter is "I" for Information. The Information group consists of all people who can influence our project in any way. This includes vendors, external architects, consultants, and similar stakeholders.

This is, as I assume, the most problematic group. They should deliver all the needed information, but there's a risk of engaging too many individuals, which can paralyze decision-making. You should select your Informers carefully. Always prepare a list of specific data you require from each person before meeting with them. Moreover, don't allow them to deliver data you didn't ask for.

Let's analyze our cases in this context.

In the CRM project, several groups can provide us with information. These range from end users to sales representatives throughout the company. We should include integrators of our sales product and the marketing team for process integration, as they work in the fluid sales process through lead generation. We can also gather insights from users of other CRM software—ideally from within our company, but external users work too. We can request more details from CRM vendors through the RFI process. Finally, we shouldn't limit ourselves to just CRM software. We should examine all software used in our sales process and consider how it might impact our CRM decisions.

Of course, this covers only the CRM side. Since we've also planned changes in architecture, delivery, and infrastructure layers, we need to identify information sources in those areas as well.

Our second case provides a good example. When delivering a new CI/CD platform, we should gather information from all users of such software across the organization. We need input from everyone the CI/CD platform might influence, such as the product manager mentioned earlier. We should also include people who want to deliver new features and need visibility into where this process currently stands.

You'll likely identify additional stakeholder groups depending on your specific case. Remember, regardless of how many information sources you identify as necessary, only start conversations with them when you've clearly defined what insights you require.

Now, we will switch to two groups related to final decision-making. First is the "A" group for "Accept" or "Approvers." This group doesn't make decisions itself, but can stop decisions. Here, we'll find compliance officers, lawyers, financial representatives, and others who regulate parts of the company connected to the project. This might also include teams like Infrastructure if, for example, you're planning on-premise software but aren't sure whether your company has the required hardware.

In our cases, this might involve approval for storing sales data in the cloud, or getting remote cloud environment costs accepted. Unlike on-premise solutions, cloud costs can vary monthly and are ongoing. It might also include approvals for licensing components used in software and infrastructure.

More importantly, when venturing into completely new territory like cloud computing, you may find that relevant regulations don't exist yet. The current team might not know how to approach these situations either. This is a common scenario. Remember to reserve time for this when planning such initiatives. Start these preparations early to ensure your project stays on schedule.

Finally, we land in "D" for "Decision" hands. This is critical, not only because it involves the person or group who will decide, but also because choosing the wrong decision maker can block your project. In the best case, it might reduce your work to something not worth your effort. Furthermore, going too high with a small project can backfire. It may appear as if you're skipping management levels, and companies often block such decisions for political reasons.

The right decision maker should be the person who will get the biggest ROI from the project. The ideal decision maker will connect with your proposition and think about it as their own. However, if you're far from the decision makers, you should carefully consider how to approach them—directly or through the hierarchy. Following the company hierarchy isn't always best for your proposition, but in some cases, it's the only way.

Engage decision makers as early as you can, deliver a valuable proposition. Get their help in engaging other stakeholders needed in the decision-making process. They will be powerful levers in moving your project forward.

What did you think about my process? Don't hesitate to leave a comment and discuss your thoughts.