Digital Sovereignty for Micro Companies

A Practical Framework for Conscious Technology Decisions

Okay, continuing from my previous two posts about digital sovereignty, I want to focus today on small and micro companies since I believe this topic matters just as much for them.

In today's hyper-connected business environment, digital tools have become the invisible backbone of virtually every operation—from the corner consultancy to the mid-sized manufacturer. Yet, I've noticed something curious in my work especially across European markets: while large corporations started in last month's investing heavily in understanding the geopolitical implications of their technology choices, micro companies often assume these considerations are either irrelevant or impossibly complex for their scale.

This assumption troubles me, particularly given the current US-EU regulatory tensions and the increasing frequency of cross-border data disputes I've observed. Just last year, I worked with a small financial firm that found out their entire client database was being stored on servers controlled by foreign governments that not fit local regulations—they only discovered this when a big contract required them to prove where their data was kept, which shocked me because this should be basic stuff for financial startups.

Digital sovereignty, fundamentally, is about maintaining control over your digital landscape. It's the ability to make conscious decisions about where your data lives, which legal frameworks govern its processing, and how technological dependencies might impact your business when geopolitical winds shift or regulations change.

Here's what I've learned and what can be useful for small businesses trying to navigate these waters: the tools and frameworks for digital sovereignty aren't complex, nor do they require significant investment. What they do require is a systematic approach and the willingness to ask uncomfortable questions about the digital tools we've grown to depend on. I have done it already for myself, and I was a bit shocked.

Have you ever considered how many of your business-critical applications are controlled by entities in a single jurisdiction? The answer might surprise you—and it's worth understanding before external circumstances force your hand. Yes, usually the answer is 90% is from the USA, and yes, it can be dangerous.

This article presents a practical framework that any micro company can implement to assess and strengthen their digital sovereignty position. Through straightforward steps involving software inventory, data classification, risk assessment, and alternatives comparison, small businesses can make informed decisions that protect their operational independence while maintaining the efficiency and cost-effectiveness that keeps them competitive.

Chapter 1: Building Your Digital Sovereignty Registry

The foundation of any meaningful digital sovereignty initiative starts with a simple truth: you can't protect what you don't understand. Most micro companies and my own isn't different here, operate surprisingly complex digital ecosystems—often accumulated organically as the business grew, with little systematic thought about where these tools come from or what they mean for long-term independence.

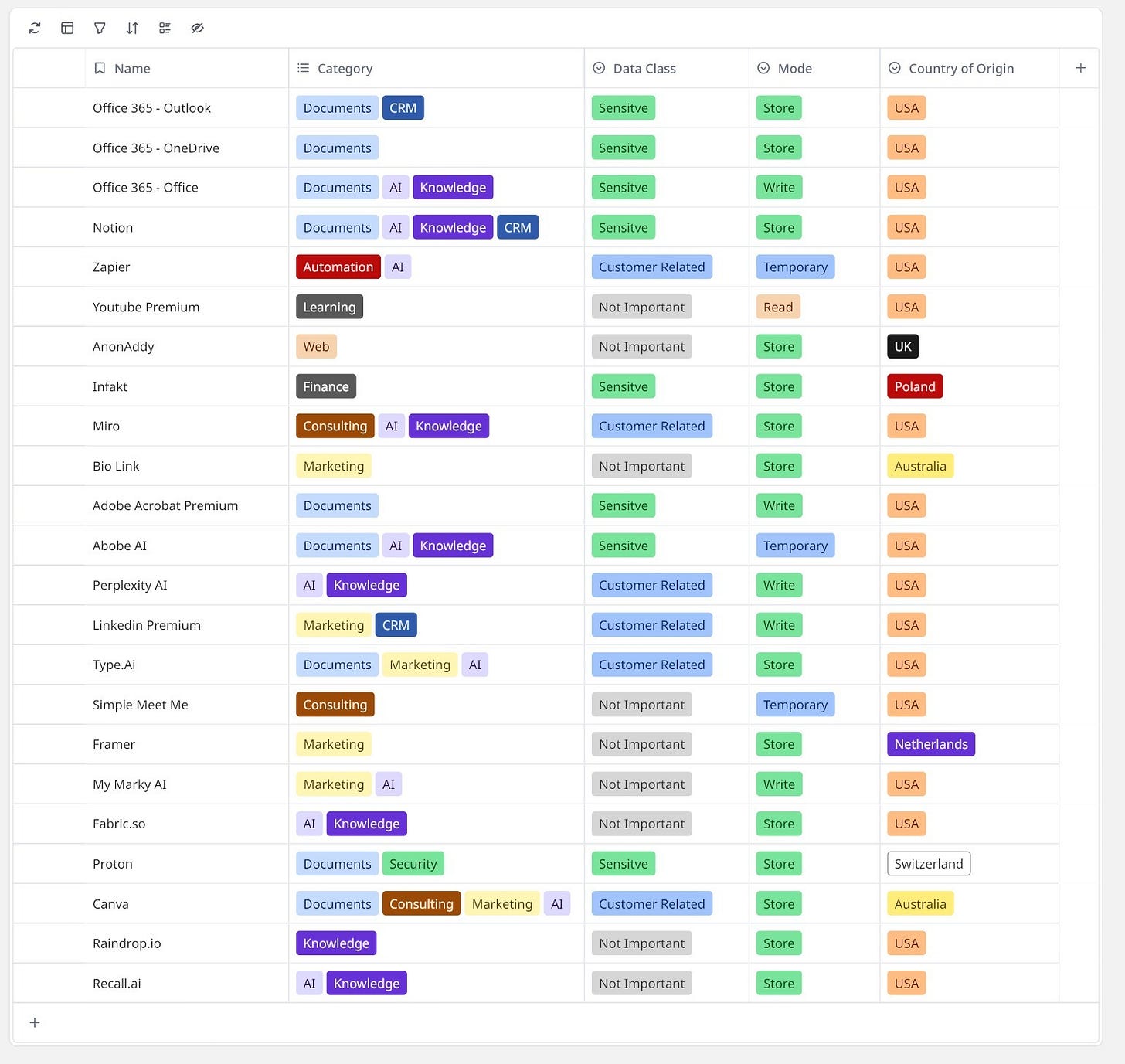

When I've mapped my digital tools, I was discovered I have using 18 different applications for my solo consulting. You can say, but you are from IT, this is why? No way, most of them are related to marketing, automation and documents management, tools that I have used for projects itself take around 20% of my portfolio. Let's look on the screenshot bellow:

Okay, having looked at output, let's look how to assess this topic and produce something like this.

Starting with Complete Visibility

Creating a comprehensive software registry serves as your digital sovereignty foundation. This isn't about building a complex database—a well-structured spreadsheet, or even table like I have done in Miro often works perfectly. The goal is complete visibility into every digital tool that touches your business, from the obvious productivity software to those specialized applications that only one person uses, but the business depends on, like invoicing.

Your registry should capture the essentials: tool name, primary function, data types it handles, and crucially—its country of origin. I organize these into logical categories that make sense for business discussions: productivity and collaboration tools, customer management systems, financial software, marketing platforms, and industry-specific applications. This categorization helps identify patterns and concentration risks that might not be obvious when looking at individual tools.

Understanding Your Data Landscape

Not all data carries the same weight, and your registry should reflect this reality. I typically work with three classifications that resonate with business leaders: sensitive data that could harm your competitive position if compromised, customer-related information that carries both business and maybe regulatory implications - in my case in consulting is about data we use in projects, and routine operational data that poses minimal risk like for example our marketing slogans.

The interaction mode matters too. Starting from applications from which you just read information's like learning resources, by applications that temporary process your data like Zapier without storing them, through application that you use to write your data like Word and other tools, finishing of applications that are end storage of your data and this data was persistent them. Understanding these distinctions helps prioritize where sovereignty improvements will have the most impact.

Making It Practical and Sustainable

My last advice, in general, start simple and build systematically. Don't aim for perfection in the first iteration - I'm sure my list isn't complete, for example, I've just recognized I have using Gitlab for storing my code and GitHub too. Focus on capturing the tools that handle your most sensitive data, most current (I haven't used code repositories in the last year) and customer information first, then expand from there.

The registry becomes a living document that evolves with your business. Regular quarterly reviews keep it current and help you catch new tools before they become deeply embedded in your operations. Most importantly, it creates a foundation for informed decision-making about digital sovereignty that's grounded in business reality rather than abstract concerns. (Strategic decisions too, but it is subject to other series of posts)

Chapter 2: Discovering Country of Origin Information

I've learned that uncovering the true jurisdictional footprint of software tools often feels like detective work—and frankly, it shouldn't be this complicated. Marketing materials rarely highlight where your data actually lives, and the global nature of modern software development creates layers of complexity that can obscure critical sovereignty information.

Let me share what I've discovered works in practice. What you can find here can be shocking, like for example "European" project management platform was actually processing data through US-based servers, despite the company's Amsterdam headquarters. This kind of jurisdictional complexity is more common than you'd expect.

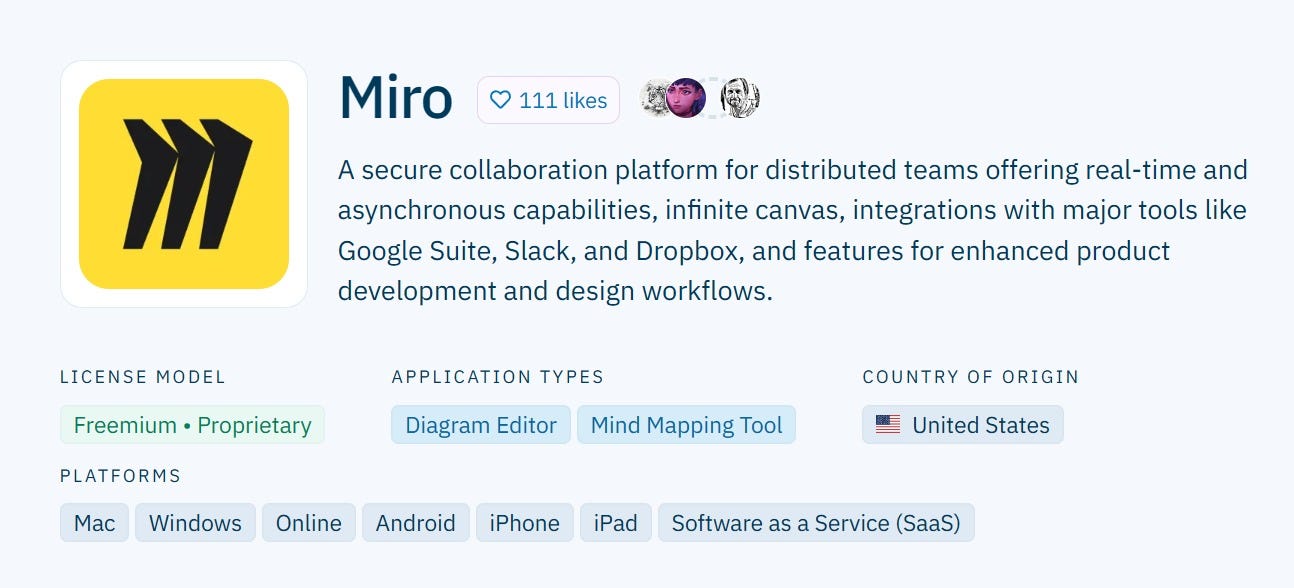

AI-powered research platforms like Perplexity have become invaluable for quickly gathering jurisdictional intelligence. I've found these tools particularly effective when you ask specific questions: "Where does Company X process customer data?" or "What's the corporate ownership structure of Platform Y?" The key is being precise about what sovereignty aspect matters most for your situation. Remember also to check sources, this is why I recommend Perplexity as it gives you links, and never believe a single source, Perplexity lies in 3 cases from my list.

The second source of truth can be Alternatives Software Databases that have evolved significantly in recent years. Platforms like AlternativeTo now frequently include country-of-origin information as well as services used behind alongside feature comparisons, which saves considerable research time. I particularly value the user-contributed insights about recent ownership changes or operational shifts that might not yet appear in official communications.

Privacy policies and terms of service contain the authoritative answers, though they require careful interpretation. I routinely look for three specific elements: data processing locations (often buried in privacy policy appendices, but you can download and ask specific questions about these subjects through AI in tools like Adobe AI or ChatPDF, even built-in Edge Browser copilot can handle it), governing law clauses in terms of service, and corporate structure information typically found in investor relations sections.

Have you ever noticed how many "European" software companies are actually subsidiaries of larger US corporations? This pattern emerged clearly during my work with financial services clients navigating post-Brexit compliance requirements. Understanding these ownership structures often matters more than the marketing narrative suggests.

Sometimes the most efficient approach is simply asking vendors directly. Most reputable companies will respond to straightforward questions about data processing locations, especially when framed around compliance requirements. I've found that mentioning GDPR compliance or sector-specific regulations usually generates helpful, detailed responses.

The goal isn't achieving perfect certainty about every jurisdictional detail—that's often impossible given the complexity of modern software architectures. Instead, focus on developing sufficient understanding to make informed decisions about your most critical sovereignty risks and opportunities. Concentrate on sensitive data mostly.

Chapter 3: Data Classification and Risk Assessment

Understanding what data flows through your digital ecosystem is where digital sovereignty moves from abstract concept to practical business reality. Not all data carries equal weight in terms of sovereignty risk. The fundamental principle is that different types of information require different levels of protection and consideration when evaluating digital sovereignty implications.

The classification approach I've developed focuses on three categories that resonate with business leaders across different sectors. Sensitive data encompasses anything that could significantly harm your competitive position or make you legal problems if accessed by unauthorized parties—strategic plans, proprietary methodologies, client negotiations, and financial details that form your competitive edge plus contracts and data under NDA. I've seen too many companies underestimate this category, only to realize later that their "routine" project management data actually contained detailed client intelligence and pricing strategies.

Customer-related data like technology stacks, projects information's, research data, etc. form the next group that, in the wrong hands, can be source of problem.

Non-critical data covers information that poses minimal risk if compromised—public materials, general research, routine administrative files. However, I always caution clients to review this classification regularly. I've witnessed situations where seemingly innocuous marketing data evolved into competitive intelligence as companies grew and market dynamics shifted.

The interaction mode adds crucial nuance to risk assessment. Applications that simply store data create concentrated but contained risks—consider them to be digital safes in specific jurisdictions. Processing applications, especially those involving AI or analytics, expose your business logic and decision-making patterns to ongoing analysis. There's a fundamental difference between a document storage service seeing your files and an AI platform learning from your strategic thinking patterns.

Have you considered how your data classification might change as your business evolves? What seems non-critical today could become competitively sensitive as you enter new markets or develop new capabilities.

Geographic considerations add another layer of complexity that's particularly relevant for European businesses. The same customer data processed within EU borders benefits from GDPR protections, while identical data processed elsewhere faces different risk exposures. Understanding these jurisdictional nuances helps prioritize where sovereignty improvements will have the most meaningful impact on both business risk and regulatory compliance.

The goal isn't perfect categorization—it's developing sufficient clarity about data sensitivity to guide informed sovereignty decisions that protect what matters most while maintaining operational efficiency.

Chapter 4: Strategic Priority Matrix for Digital Sovereignty

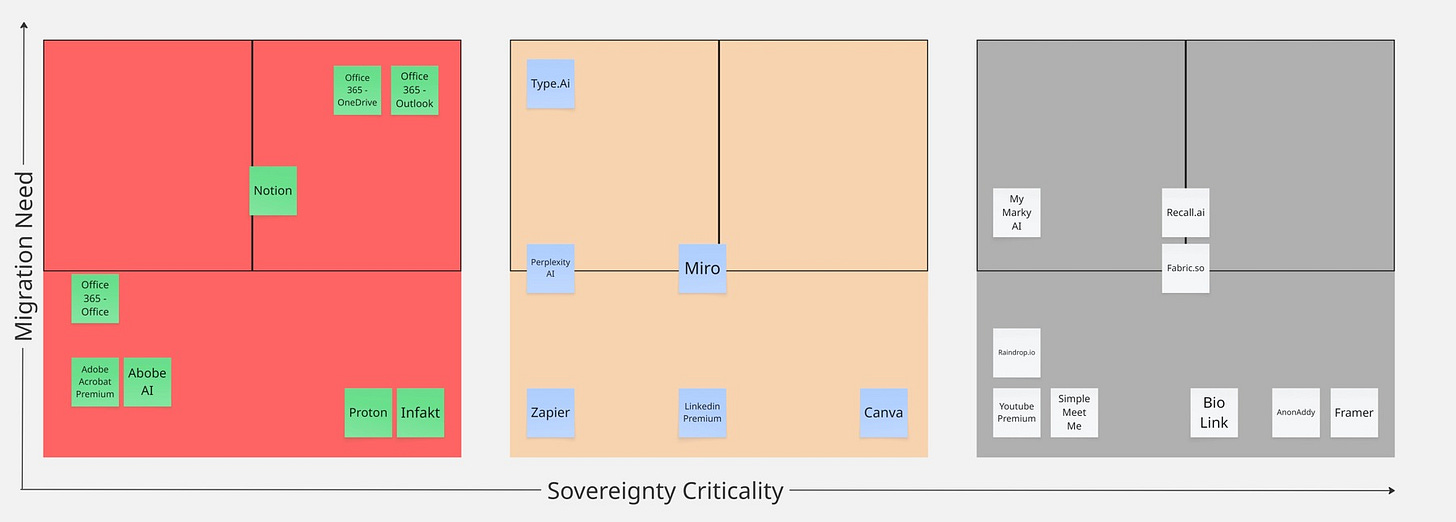

Once you've mapped your digital landscape and understood your data flows, the real strategic work begins: deciding where to focus your limited time and resources. I've learned is that trying to address everything at once is a recipe for paralysis. What you need is a clear framework for prioritization.

The strategic priority matrix I developed addresses exactly this situation. It plots each application along two dimensions that matter most for practical decision-making: sovereignty criticality and migration feasibility. Think of it as your strategic compass for navigating these waters without drowning in complexity.

Understanding the Four Quadrants

High Sovereignty Criticality, Migration Required - These are your urgent priorities. Applications that pose real sovereignty risks and require immediate attention through replacement or significant modification. In my experience, tools handling sensitive customer data or proprietary business information often fall here—especially when they're processed in jurisdictions that conflict with your compliance requirements or business risk tolerance.

High Sovereignty Criticality, Migration Not Needed - This quadrant represents your acceptable risks. These tools may handle sensitive data but already meet your sovereignty requirements through favorable jurisdictions, adequate data protection, or acceptable risk profiles. I worked with a fintech startup that discovered their core banking integration platform fell into this category—high criticality but already compliant with their sovereignty needs, this should be the usual mode for your very critical systems like core banking is for financial institutions.

Low Sovereignty Criticality, Migration Required - These represent opportunities for gradual improvement. While not urgent from a sovereignty perspective, these tools may need replacement for other business reasons—cost optimization, feature requirements, or integration needs. I often recommend addressing sovereignty considerations during these routine business-driven migrations.

Low Sovereignty Criticality, Migration Not Needed - Generally, leave these alone unless circumstances change dramatically or other factors like pricing or better functionality moves you to make changes. These tools pose minimal sovereignty risk and function adequately for business needs.

The matrix isn't just a planning tool—it's a communication framework. I've found it particularly effective when explaining sovereignty trade-offs to business stakeholders who need to understand why we're prioritizing certain changes over others. It transforms abstract sovereignty concerns into concrete business decisions.

Remember, this assessment evolves with your business and the geopolitical landscape. What seemed low-risk last year might shift categories as regulations change or as your company handles more sensitive data. I recommend quarterly reviews to keep your priorities aligned with current realities.

The goal isn't achieving perfect sovereignty across every application—it's making conscious, informed decisions about where sovereignty matters most and where practical alternatives exist to reduce risk while maintaining the operational effectiveness that keeps your business competitive.

Chapter 5: Feature Comparison and Replacement Strategy

When you've found apps that need to be replaced for better control, you're entering the trickiest part of the whole process. This isn't just about finding tools from different countries—it's about making sure that better control doesn't accidentally break your business.

The key to any good replacement plan is writing down not just what your current apps do, but how they work with everything else in your business. I've noticed that many business leaders can describe what their software does, but have trouble explaining the small workflow connections that keep their operations running smoothly.

Start by listing the specific things each app does—not just the obvious features, but how it connects to other tools, what data formats it uses, which parts of the interface your team relies on, and how fast it needs to be for daily work. For a CRM system, this might include not just managing contacts, but how it works with email, report formats that go into board presentations, or mobile access that supports field sales. For example, my email provider has to work with automation systems like Zapier—I use it heavily and can't live without it.

This detailed understanding is crucial because alternatives with better control rarely offer the exact same features. They might do similar things in completely different ways, or they might be great at things your current tool handles poorly while missing features you've grown to depend on. The key is telling the difference between truly needed capabilities and those that are just convenient.

Newer apps often offer better control but may lack the completeness, reliability, or connections of established tools. For business-critical apps, this trade-off requires careful thought about both control benefits and operational risks.

I've found that successful replacement plans share several traits. They start with apps that offer the best mix of better control and easy implementation. They account for business continuity needs, often involving running both systems during transition periods. And they recognize that perfect control may not be possible or necessary for all apps.

Have you thought about how your team's productivity might be affected during the switch? In my experience, even small interface changes can temporarily reduce efficiency, and this impact should be factored into your timeline.

Sometimes mixed approaches work better than complete replacement. This might involve using better-controlled tools for sensitive data while keeping existing apps for less critical functions, or setting up data workflows that minimize control exposure while maintaining necessary connections.

The goal isn't achieving perfect control across every app—it's making smart improvements that meaningfully reduce risk while preserving the operational effectiveness that keeps your business competitive. Success in this phase requires balancing control objectives with practical business needs, recognizing that the best solution is often the one that improves your control while maintaining the workflows your team depends on.

Conclusion

Digital sovereignty for micro companies isn't just another compliance checkbox—it's fundamentally about maintaining the freedom to make strategic decisions without external technological constraints.

The framework I've outlined here emerged from practical necessity rather than theoretical planning.

What strikes me most about successful digital sovereignty initiatives is their evolutionary nature. The companies that thrive don't attempt perfect sovereignty overnight. Instead, they build awareness, make informed trade-offs, and gradually strengthen their position as opportunities arise.

The tools and techniques presented here are intentionally accessible. Your registry can live in a spreadsheet. Country of origin research requires nothing more than careful online investigation. The priority matrix needs no specialized software. This accessibility is deliberate—digital sovereignty shouldn't require enterprise-grade resources to implement effectively.

Perhaps the most important insight from this work is recognizing that digital sovereignty decisions are fundamentally human decisions. They reflect our values of independence, our tolerance for risk, and our vision for how we want to operate in an interconnected world. I've noticed that companies with the strongest sovereignty positions are those where leadership has thoughtfully considered these questions rather than simply sticking to the most convenient or cost-effective options.

The framework adapts to your specific context because every business faces different constraints and priorities. A fintech startup operating under strict regulatory oversight will make different sovereignty trade-offs than a creative agency focused on international collaboration. The key is making these decisions consciously rather than by default.

As geopolitical tensions continue reshaping the digital landscape, micro companies that understand their technological dependencies will find themselves better positioned to navigate uncertainty. The investment in sovereignty analysis pays dividends beyond immediate risk reduction—it creates organizational capability for evaluating technology decisions strategically rather than reactively.

Have you considered how your current digital choices might limit your strategic options five years from now? The companies I work with that ask this question early tend to maintain more flexibility as they grow and as external circumstances evolve.

The journey toward digital sovereignty begins with awareness and progresses through systematic improvement. Even modest steps—understanding your current dependencies, classifying your data sensitivity, identifying concentration risks—provide valuable foundation for future decisions. The goal isn't achieving perfect sovereignty across every application, but rather making conscious choices that preserve your operational independence while maintaining the efficiency that keeps you competitive.

I've for example decided to stay and even consolidate some solutions to Notion, stay with Miro when testing Nova Tools as Spain-Canada based alternative, and obligatory stay with Office 365 even for Document Storage I've decided to move this part out to Proton Drive which feels for me as much more secure for formal documents.